The aim of this essay is to discuss the methods for describing and analysing movements that Loke and the colleagues (2005, 2010), introduce in their papers. In addition, it will analyse if and how they are useful when it comes to designing new movements within the field of technology. In order to analyse the above-mentioned matters, this essay will compare them with the experience gained from a design project. This design project was part of a university course, whose objective was to explore different movements and their experiences while working with machine learning.

We experience the world with our bodies. They allow us to interact with objects around us, through movements. For a while, movements and gestures has been used within technology to create better interactivity. This can make the interaction more intuitive and natural. For example, we can take the finger gestures used on our smartphones, swiping, typing and so forth. In their paper Loke & Robertson (2010) explain how the interactive technologies that are becoming more embedded in our daily lives, are movement-based, which leads them to be more sought after. Consequently, designers try to design new movements for those technologies. Those new movements should be described or analysed after they are created, because it can inspire and make the designing process more fun as presented later. Loke and the colleagues (2005, 2010) present two ways movement-based interaction can be worked with through describing the movement itself. The first method is through three perspectives: “The mover”, “The observer” and “The machine”. The second method is describing by using Labanotation. These methods will be applied on the project which was about exploring and designing new movements through machine learning. It explored the topic of baseball and the different types of baseball pitches.

Loke and Robertson (2010), conducted two studies in which they tested out movements with dancers and contributed few methods that interaction designers can work with the moving body. In order to move through them they introduce three perspectives -“The mover” – which offers the first-person experience of the gestures, “The observer” – this perspective provides a view of the body and experience from outside standpoint; and last but not least “The machine”- this perspective offers to see how the machine itself recognises the movement. Through these perspectives they set up the three techniques that are used through first person view: “Playing with Everyday Movements and Gestures”, “Scoring” and “Generating movement from Imagery”.

Each technique has its own principles to follow. Loke and Robertson (2010) explain how direction or speed of the movement can inspire designers to explore more possibilities when designing a certain movement. During the experiment phase of the project, while testing out the code and how it works, some of these techniques were used in order to explore different movements. Working with Machine learning we were able to observe from the Machine’s perspective as well. We started by experimenting with the first technique “Playing with Everyday Movements and Gestures”. While testing out movements, it allowed us to be more intuitive with the changes in the movement. For example, the gesture of twisting the arms, turned more into wave like movement. Moreover, we added different heights to “the wave” gesture. I tried working with different speeds and then comparing the results, by focusing on what was recognised from the machine and what not, in order to do different variations of the same movement.

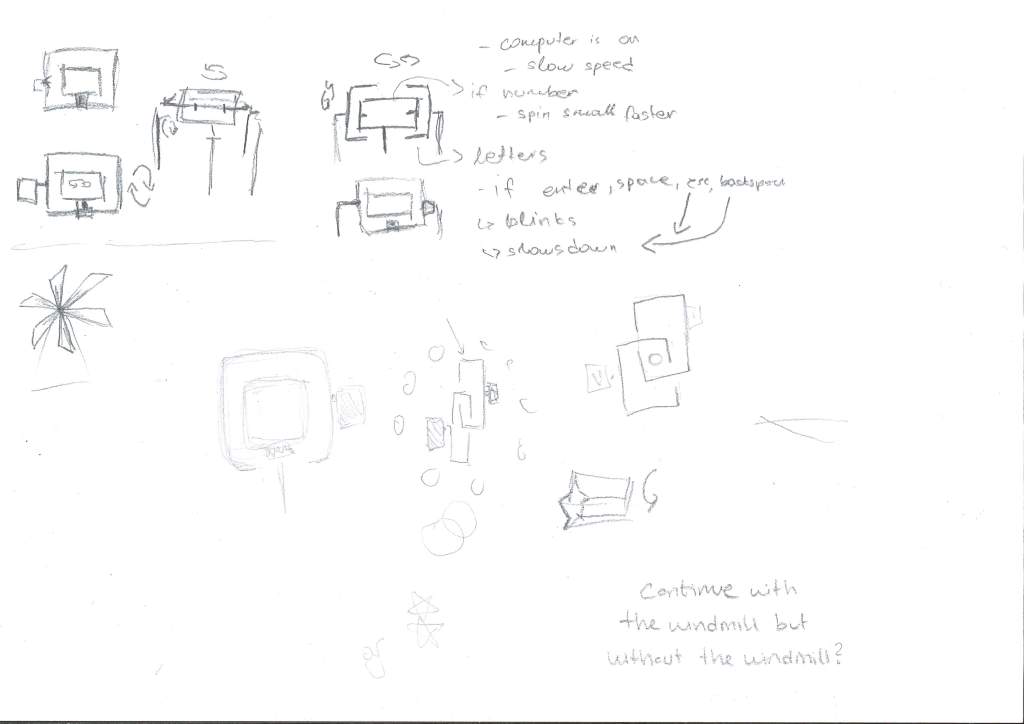

With these techniques we can also express movements or choreographed ideas through combining text, sketching and images. According to Loke and Robertson (2010) it can be used as another way to represent an idea or even have an inspirational role. We documented our movements in two ways: Through using written descriptions and visual representation of it such as videos and images. I did not find describing the movement with text much of an inspiration for the project. There was no huge impact on the way we designed or improved the movements we explored. Since it is not an everyday activity, the text description was mostly confusing. According to Loke and Robertson (2010, p. 10), the written descriptions are a “written record of the choreographed movement, that details the specifics of how the body moves, the motivation for the movement and the kind of act in which the movement is contained.” Explaining and writing a description of the movements was a challenge. We found it challenging to figure out how does one describe a movement. Even though it did offer a view from two different perspectives, one of my teammate as the “mover” and one from me as an observer, I did could not find it as useful as the visual documentation, which is explained more in depth below.

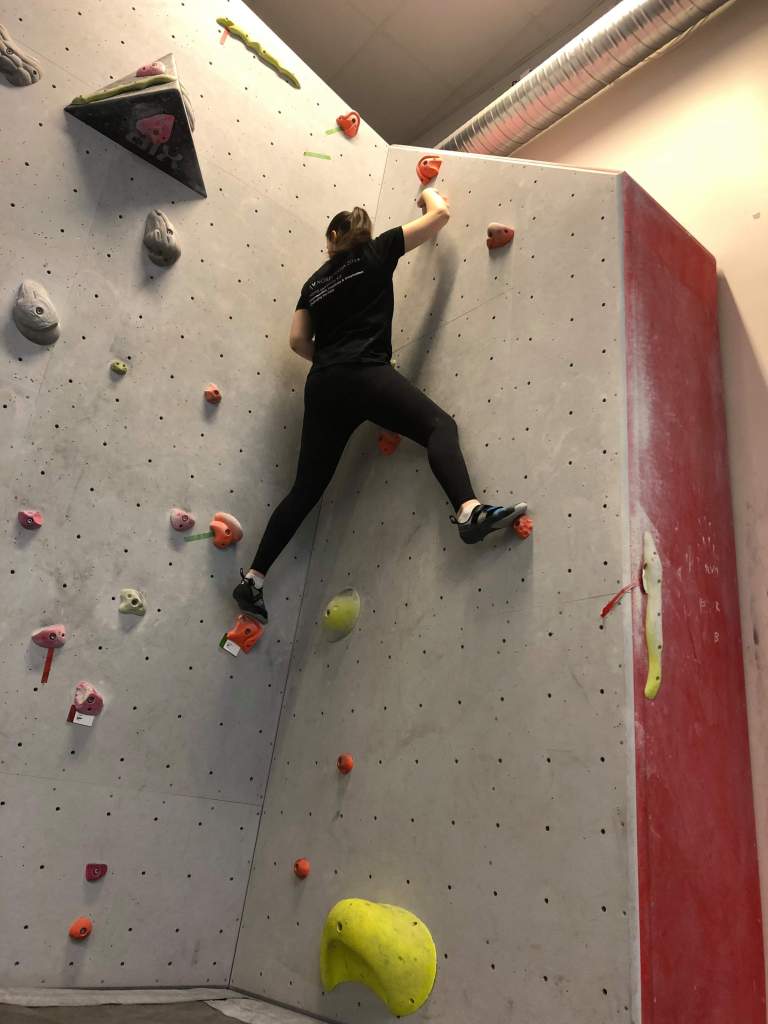

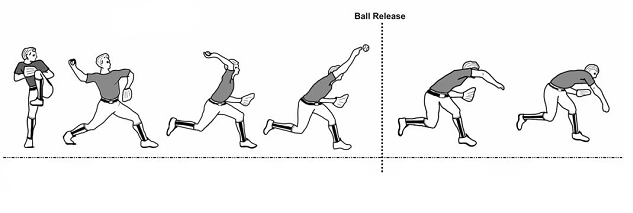

Videos and images on the other hand, did help me open up my imagination of what changes can be done in a movement. Maybe we did not gained much with worded explanations, but images give the option of visualizing and understanding a movement. It helped with understanding how the speed influences the movement itself and when we had to detect small details that are usually missed. We found the visual documentation also quite handy when recording the movement with sensors. Watching the video of the first recordings we realised the speed was quite fast and as a consequence the machine could not figure out the difference. Breaking down the video from the movement into small segments, did help with analysing it. Splitting the movement into parts and later analysing is called Shape Analysis. “The Shape analysis is a description of the changing forms and spatial qualities of the moving body.” (Loke & Robertson, 2010, p. 11). When analysing the movement, it can be split into different shapes, to gain a better understanding of what that movement is created from. In their paper, the authors analyse a movement where the transition of the body starts from what they call “ball-like” position to a splayed “wall – like” position on the floor and back to curled up position. The shape analysis done during the project, presented us with insights as to which part of the movement can be recorded in order to get more useful results.

In addition to what was mentioned above, “A movement can be performed with kinetic variations of speed, scale, and direction to produce different patterns, dynamics and qualities of movement” (Loke & Robertson, 2010, p. 13). As previously mentioned, speed was one of the most important factors when we were recording. The faster the movement was, the more difficult it was for the machine to recognise it. The differences in speed or scale created a possibility to create new variations from the same movement. Since the machine perspective is not the same as the mover’s or observer’s perspective these variations can be important for the recognition in machine learning. In our project it showed that the small differences in the movement such as moving the arms differently and doing the movement with speed can affect how machine recognise it later. Consequently, the quality of data is being affected. Through experimenting and recording movements, it showed that sensor placement matters. Better placement such as sensors on the arms, and slower speed led to more accurate results and machine recognition.

Labanotation is the second method data can be described and analysed with. According to Hutchinson (1977), “Labanotation is a system of analysing and recording movement, originally devised by Rudolf Laban in the 1920’s and further developed by Hutchinson and others at the Dance Notation Bureau, New York “ (as cited in Loke et al., 2005, p. 114). When creating interactions for input, Loke, Larssen, and Robertson (2005) find Labanotation as a potential tool that can be used for analysing and notation of the movements. They argue that this can provide a good starting foundation when designing a movement-based interaction. “There are three essential forms of movement description in Labanotation – Motif, Effort-Shape and Structural” (Loke et al., 2005, p. 144). Following the definitions in the paper we can describe them as the following: The form of describing only the main parts of the movement or the motivation behind it is called Motif. When describing the aesthetic, emotional and expressive qualities we use Effort-Shape. Last but not the least when we want to describe a movement in a most specific description, we use the Structural form. Most of our movements in the project were described using the Motif. The reason for using that form in specific was that it was a project where the final outcome was not the goal rather than exploring and trying to design new movements. The simple analysis provided us with descriptions fast enough to move forward with our project. The disadvantages of this form were the lack of details in the description of the movements. We never went to explore how the movements would feel like if we changed how the movements look like or what exactly they are expressing rather than where the hands go when throwing the ball. We also learned that the act of describing a movement based on its components and the motivation behind it can be challenging without a proper research of the movement itself. We noticed that before we did background research on the types of pitching movements, it was challenging to describe what was the motif rather than a simple ball throw. The research of the topic made the description to be easier.

All things taken into consideration, the methods that Loke and the colleagues (2005, 2010) mention in their papers about describing and analysing movements, are useful in the process of designing movement-based interaction. They inspire and guide us throughout the process of designing, which can be chaotic and messy sometimes. Some of them such as the three different perspectives can be used in different scenarios, such as machine learning and movement-based interaction with technology. Documentation is important for movement-design, as it inspires, sand it can be handy to look back at the iterations of the movement. Even though text documenting was not useful for us, it might be useful for other people. Visual documentation on the other hand opens better imagination through visualisation. In addition, analysis with Labanotation is effective for good analysis of a movement. Its three different forms can be used for thorough analysis. Depending on how in-depth and detailed we want the analysis to be, each of these forms can help when we try to achieve a certain goal. As stated by Loke, Larssen, and Robertson (2005, p. 120) “Labanotation and its underlying movement analysis system offer an understanding of the moving body and its movement potential that can act as a foundation for the design of movement-based interaction.”. With this base, the path for merging movements and interaction with technology is wide open.

Reference list

Loke, L., Larssen, A. T., & Robertson, T. (2005). Labanotation for Design of Movement-Based Interaction. Second Australasian Conference on Interactive Entertainment, 1996(November 2005), 113–120.

Loke, L., & Robertson, T. (2010). Studies of dancers: Moving from experience to interaction design. International Journal of Design, 4(2), 1–16.